‘Eliminating stigma against people in recovery appears to be a universally supported goal within the recovery community, and for good reason. Recovery is hard enough without this additional burden.

‘Eliminating stigma against people in recovery appears to be a universally supported goal within the recovery community, and for good reason. Recovery is hard enough without this additional burden.

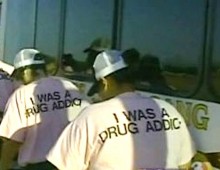

The unspoken assumption is that stigma is the fault of the “outside” world – not of other people in recovery. But the recovery community has failed to provide effective leadership on this issue. And one component of the community—treatment providers—frequently reinforces stigma. How can we expect the world at large to change when we don’t change?

I operate a treatment system with two residential facilities, a sober living home and outpatient services. Because relapse is common, we often see clients who have been to other facilities. Most are frustrated, and often furious, at how they have been treated elsewhere. They generally report that they were viewed by staff as entirely lacking good judgment or a capacity for self-management. Therefore their requests and perspectives were easy to dismiss, even ridicule. They often have not been treated with much hospitality, either.

In short, they report just what you would expect to hear from anyone who is a member of a stigmatized minority. In the US treatment community, someone with a history of impaired control over addictive behavior apparently does not merit basic respect. All of their decisions – not just the decisions around addiction – are viewed as bad ones. It should go without saying that addictive behavior decisions are by no means intrinsically bad, and in any case what matters in treatment is examining their meaning to the person who made them.

To illustrate how rehabs stigmatize, consider these four experiences related to me by four of my clients.

1. One client reported being in a well-known $1,500-per-day East Coast facility where he shared a bathroom with two other people and the food was brought in by an outside vendor, often arriving too early so it was cold at mealtime. There was almost no scheduled free time, with groups and mutual-help meetings every night. Church attendance was also required, something that prior to admission the client had not been informed of.

“I thought I’d have some time to think. After all, I’m trying to make big changes in my life,” he said. “But they kept me so busy it was very hard to come to my own judgments about what I was hearing. Maybe that was the point, to prevent me from thinking?”

Allowances might be made for these aspects of the facility if the treatment had been outstanding, but there were only one or two individual sessions per week, and the counselors were not professionally trained.

I often see clients who are frustrated, and often furious, at how they have been treated at other rehabs. They were viewed by staff as lacking good judgment or a capacity for self-management. Therefore their requests and perspectives were easy to dismiss, even ridicule. In short, they report just what you would expect to hear from anyone who is a member of a stigmatized minority.

Despite all that busy-ness, my client said that almost no attention was paid to what he defined as his primary issue: developing a new direction in life after some recent major situational changes, which he had coped with by drinking rather than adapting. He left the rehab after a few days, furious about being misled and ignored.

This experience left him uncertain that good substance-use treatment existed anywhere. Most disturbing, because early recovery is time of great vulnerability, a part of him believed that he actually deserved to be treated badly—that he deserved to be stigmatized. Fortunately he found the inner strength to keep looking for a different approach.

2. Another client reported that she arrived at a large, nationally known facility after lengthy travel and, after completing check-in, asked to take a walk outside to transition into settling into this new environment. The answer was no.

“I thought, ‘Of course, they don’t know me, so they are concerned about my safety and the safety of the facility,” she told me. She asked if another, established resident could provide an escort? “No.” Could a staff member provide an escort? “No, you’ve been getting what you want for too long,” she was told. She asked to meet with another staff member, who told her in essence that the purpose of treatment was to drive home the idea that “you can’t have everything your way.”

She quickly decided (she was also someone with a fair amount of internal strength) that to be seen as an “addict” who “only wants everything her way” was not going to help her develop better judgment about how to live her life.

3. A third client spent 30 days in a large, regionally known rehab and was berated the entire time. As he described it, every time he spoke up about his own perspective about himself, his behavior, his situation or almost any other topic, he was told, directly or indirectly, that as an “addict,” his perspective could not possibly have any validity.

At discharge the prognosis was pessimistic. “It is hard to see how you can be successful in recovery,” he was informed. “You are working your own program, not the program we are presenting, which is the only program that could ever work for you.”

The client had in fact done considerable work on his own before and during rehab reflecting to establish a foundation for why change was desirable. He also established what turned out to be a solid approach to maintaining recovery, which included follow-up outpatient treatment (where I encountered him). In the face of an entire facility’s “professionals” questioning his ideas, he was able to muster the confidence to trust his own judgment. But the burden of coping with these imposed doubts was difficult, and many people lack this client’s inner strength.

“No one there seemed to care about what I thought, what I valued or how I planned to change. It was their way or the highway,” he said. “I’m actually a very moral person. I had allowed my life to lapse into a level of immorality, because of my drug use, that now shocks me. It shocked me enough to change.”

4. “Rehab was a beautifully furnished jail,” a fourth client told me. “The schedule was about killing time all day.”

The groups were led by untrained staff who were considered qualified only by the fact of their own recovery. They did not engage her, she said, because they were rote and repetitive. She got 30 to 60 minutes per week with a trained professional.

This particular rehab, which is the priciest of the four mentioned here, is well known in the industry. If someone is dissatisfied by her experience at a rehab with “not much program” and wanted to attend a facility with “a good program,” this facility is likely to be recommended. But my client left feeling deeply confused about what recovery was really about, and more confused about herself than before her admission.

I have heard versions of these four stories many, many times. Taken together, they describe a rehab industry that often appears more punitive than therapeutic and is generally lacking in basic human values.

The active stigmatization of clients by rehabs begins even before an individual is admitted—by rehabs’ practice of misrepresenting what they offer. Many are intentionally misleading. Given their manifest contempt for “addicts” and “alcoholics,” they have no ethical qualms about deceiving potential clients. “They are all in denial anyway, so who cares what they think!”

Is it acceptable to overcharge, to require church attendance and to offer no individualized treatment? Only if you have little respect for clients.

Is it acceptable to deny even small reasonable requests as a form of training and to attempt to have complete control of someone? Only if you think that clients are not capable of any self-management.

Is it acceptable to ridicule the client’s perspective on how to recover? Only if you think that the client knows nothing about how to recover.

Is it acceptable to invest far more resources on having expensive furnishings than on having an adequate number of professional treatment providers? Only if you think that clients are not intelligent enough to tell the difference between effective and ineffective staff and choose a particular rehab based entirely on its status, look or comfort level.

Is it acceptable to offer “treatment” that consists almost entirely in putting all clients in the same set of groups, with little attention paid to individual concerns? Only if you think of clients as “addicts” and “alcoholics” who are all the same and can be treated as such.

The active stigmatization of clients by rehabs begins even before an individual is admitted – by rehabs’ practice of misrepresenting what they offer. These four individuals did their best to investigate how the rehab operated before choosing it. Many rehabs, however, are intentionally misleading, and they find it perfectly acceptable to be so. Of course they do. Given their manifest contempt for “addicts” and “alcoholics,” they have no ethical qualms about deceiving potential clients. “They are all in denial anyway, so who cares what they think!”

I have read the websites of these facilities. If the admissions coordinator repeats to prospective clients the same information that is on the website, clients are kept completely clueless about how the rehab actually operates. Telling the truth would make for a much harder sell.

Until the rehab industry cleans up its act and takes addiction treatment seriously, it will continue to increase rather than reduce stigma. Where to begin the improvement?

We could start by dropping the labels of “addict” and “alcoholic” (unless the client has freely chosen the label) and by focusing on the unique needs of each client. Then treatment providers could offer individualized – and more effective – treatment, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach for an entire stigmatized class of people.’

This article was on the substance.com website.